Making it a habit

/At the beginning of each new year, many of us resolve to change something in our lives.

It could be going to the gym more, taking up a new pastime, losing weight, putting more money into super, or committing to seeing those friends we’ve neglected over what’s been the most testing of times.

Studies have shown that 80 per cent of new year’s resolutions fail, and as we approach the second quarter of the new year it’s likely that any new habits you’d like to form have begun to wane.

But the good news is that forming new habits – and sticking to them – is very achievable: all that’s needed is a strategic approach, and an understanding of how the mind – and body – adapts to something new.

Understand why you’re doing it

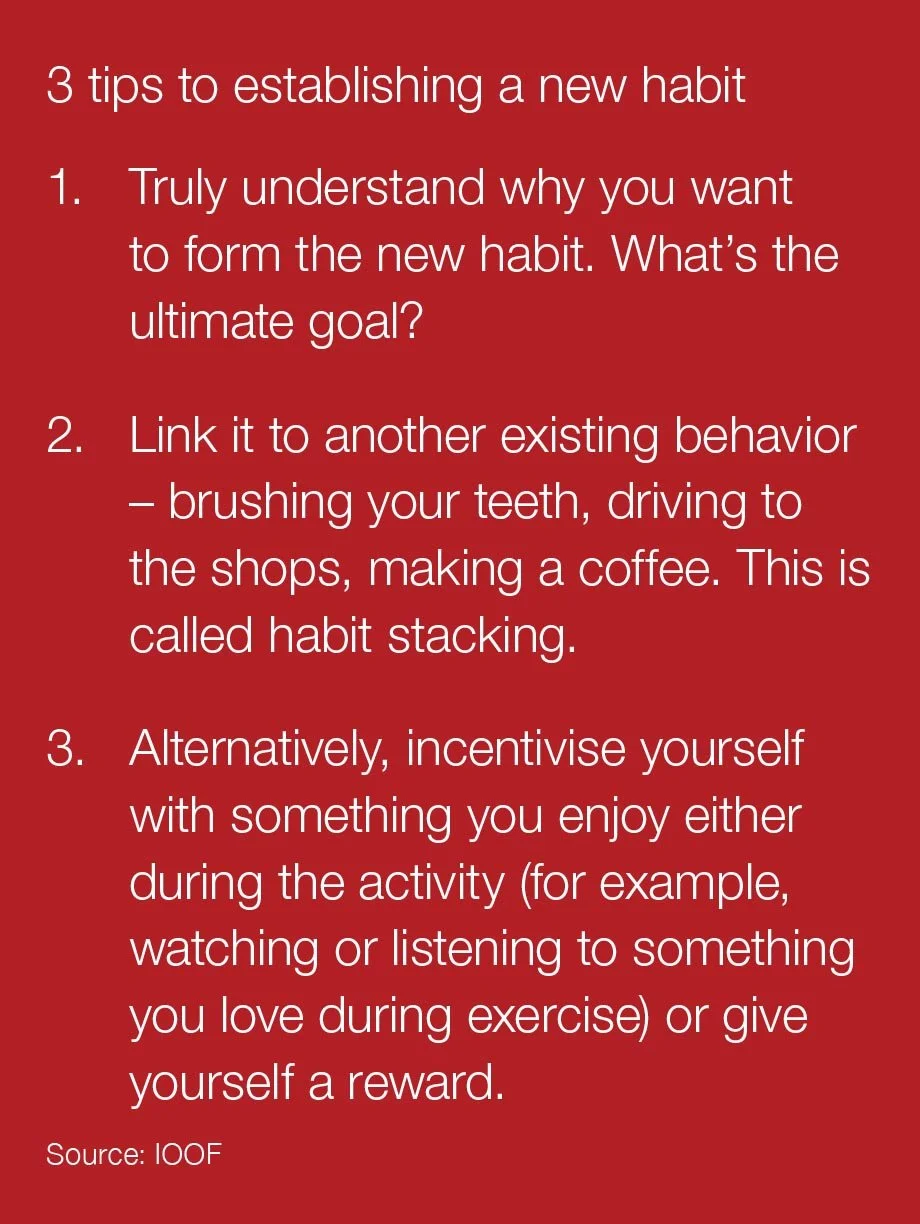

What’s the genuine reason for wanting to form that new habit? If you’re wanting to take up lawn bowls for example, is it because of the sport, the people you’ll meet there, or getting outdoors? If you’re wanting to form new financial habits, such as sticking to a budget, what does that mean for you and your personal situation in the long-term? What’s the incentive? If you can drill down to get to the true why, and visualise how you’ll feel, and what you’ll have accomplished by sticking with it, you’ll have the motivation to form a new habit.

There are no shortcuts – new habits need to be worked at!

We’d all love to decide to eat more healthily and, voila, it happens automatically. Unfortunately, however, it’s just not that straightforward! Studies have shown that forming new habits begins with consciously doing the thing we want to become a habit, and then performing that behaviour frequently and consistently.

It can take anything from just over two weeks to the best part of a year to form a new habit – with an average of 66 days needed for something new to become ingrained. But the reality is that it’s not until a new routine becomes automatic that habits are formed – and there’s no shortcut!

Give your new habit context

Associating a new routine (something you’d like to become a habit) with something you already automatically do (an existing habit) can also increase the chances of success.

For example, if you want to get into the habit of drinking more water, consciously choosing to have water with breakfast every morning will increase the chances of it becoming a habit. This is because you’re anchoring it to an event or giving it a context: the new ‘habit’ becomes part of something else.

This is called habit stacking.

It works on a principle that before or after you perform an existing habit, you add a new habit to it. For example, before you have your first cup of coffee of the day [existing habit], you’ll stretch for five minutes [new habit].

You can join new habits with existing ones, too. For example, if you’re a sucker for a renovation show, you can commit to watching one per day – while on the exercise bike or treadmill. If you love listening to a particular podcast, resolve to listen only when on your morning walk.

By connecting something we enjoy doing with an activity we want to become a habit, we can increase our chances of it sticking.

How habits are formed: the science

Of course, our brains are key to forming new habits, and it’s the connections – neural pathways – between neurons that are responsible.

Essentially, the more we perform a task or a routine, the stronger the neural pathway between neurons gets. Neuroscientists found that the brain chunks together the individual components of a habit (for washing your hands, for example, think turning on the tap, dispensing soap, washing, turning off the tap and drying) and that certain neurons in the brain initiate and end the sequence of tasks that make up the habit.

A study from researchers at the University of California in San Diego identified certain brain chemicals and neural pathways that were involved in switching between behaviour that was habitual, and actions that were deliberately taken.

They said the findings provided strong evidence to suggest that those neural pathways competed for control of the orbitofrontal cortex – the area of the brain which makes decisions – and that the endocannabinoids neurochemicals moderated goal-focused circuits.

The research into truly understanding how the brain adapts to changing habits is still in its infancy, but what we do know is this: to maintain a new habit, you’ve got to consciously do it, repetitively, until it’s something that happens naturally.

And, by fully understanding your motivation for doing it, you’ll have a strong incentive to stick with it.